This week’s readings were selected and grouped together in order to explore combatant and civilian perspectives during the First World War. By examining the tensions in these perspectives, we might complicate our notions of how war is both physically and psychologically experienced by all involved—those on the front lines and those on the home front. The massive scale of loss during the “Great War” catastrophically altered nations, and the corresponding sense of social fragmentation and alienation had a transformative effect on individual perspectives and artistic practices during and after the war, a cultural shift or era that we now call modernism.

Readers often struggle to assemble a coherent understanding of the meanings found in modernist texts like The Waste Land. The process of breaking down the fragments of Eliot's text in relationship to the whole (such as, the “whole text”)—the style, language, and structure, the seemingly disjointed barrage of images and allusions, and the difficulty of locating a coherent speaker or voice—impresses upon the reader the mental anguish and confusion experienced by so many during this time period. We are disorientated when encountering the landscape of The Waste Land just as the poem's various speakers are disorientated by the world that they are attempting to understand; just as the speakers are in some way attempting to (re)construct new meanings, new understandings, and new ways of representing a world now altered, we too as readers are asked to construct or engage in new ways of approaching poetry (or fiction, as we’ll explore later with Joyce, Woolf, and Conrad). To help understand why high modernist texts like those by Eliot and Loy seem so obscure, we should accept that these writers were not so much trying to be difficult just for the sake of being difficult. Rather, writing in this way created something new out of something that felt so empty and hollow. This directly links to the influential American poet Ezra Pound’s imperative to his fellow modernist artists: “Make it new.” (NB: Eliot and Loy are also often categorized as American poets, and are often included in both American and British literature surveys. Eliot was an American expat living in England for much of his career and Loy was originally from England, lived as an expat in Europe, and eventually became an American citizen.)

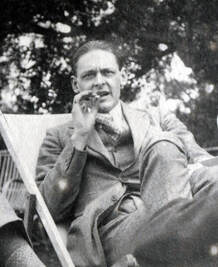

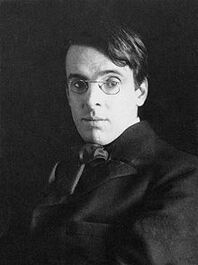

| T. S. Eliot in 1923, by Lady Ottoline Morrell | Image Credits: Wikipedia | William Butler Yeats photographed in 1903 by Alice Boughton |

It should be said, however, that modernists did not necessarily refer to themselves as modernists. We should keep in mind that categories used to define a specific time period and style are almost always retrogressive, or applied by later readers/scholars, because of course when you’re living and creating art in the midst of such cultural revolution you are typically not aware of the whole, or how your work connects to the whole production of culture during that time. Such things can only be seen in hindsight, though I do think Pound and others were quite conscious of a dramatic shift in literary representation and style due to the dramatic social and technological changes occurring during this time of rapid modernization, and many were interested in questioning and defining what it meant to be “modern.” For our immediate purposes this week, we should consider in our readings of the assigned texts how modernist literature was directly linked to the devastations of the war, or, a wartime climate that had not been experienced on such a vast, global stage with such vast, global consequences prior to the twentieth century.

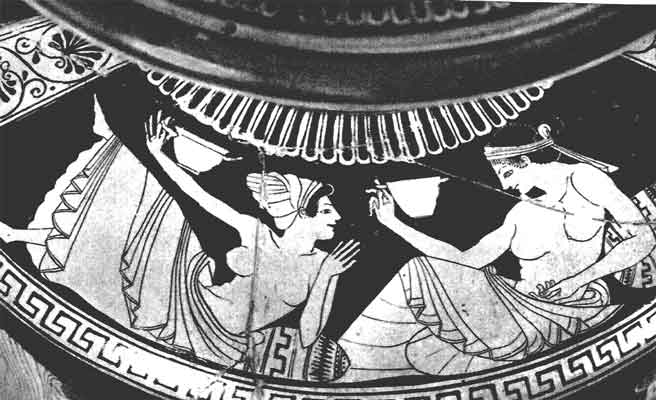

Thus, Yeats, who in some ways views himself as a visionary prophet, seems to see only further destruction to come, or at least further darkness; all the old consolatory myths (such as those found in religion) cannot be relied upon to make sense of the new world order, since religion itself, as Yeats seems to imply, has been responsible for such cataclysmic events. At the same time, in “The Second Coming,” Yeats relies on the same biblical myth of apocalypse that he is critiquing in order to construct the terrain of his poem. For Eliot, the broken land and broken, hollow people who appear to be no more than walking corpses, trapped in the Underworld (of a devastated London), indicates a broken culture; rather, all the old fragments of culture—religion, myth, and literary tradition—are no longer sufficient or capable of providing sense and unity. Yet, much like Yeats and to a far greater extent, Eliot’s poem is constructed entirely of that broken culture, and as the primary speaker of the text claims, to “shore up these fragments against my ruin” might be the only way to salvage something and create something new. Because, in Eliot’s view, it is culture and all the art and “higher” thinking/forms of creation that humans are capable of which remain key to the survival of civilization in the face of such wide-scale destruction. Art and culture is what “civilizes” us, or so this seems to be the prayer that Eliot is offering, just as the poem ends in a prayer, “Shantih Shantih Shantih,” a plea for “the peace that passeth understanding.”

Granted, Eliot has been accused of elitism and cultural snobbery (not to mention racism and sexism), and nearly a hundred years after the publication of The Waste Land, we have yet to see if literature and art are capable of saving us from ourselves. I would like to believe there is some truth and value to Eliot’s fervent faith in culture as salvation/redemption (from our own brutal potential for violence, hatred, xenophobia, and destruction), though I’m probably far too influenced by a postmodernist or even posthumanist point of view to buy into the investment in such grand narratives or “truths” that Eliot would like to recover. I will give him credit, though, for being hopeful—and in my opinion, out of all the poems we’ve read this week, Eliot’s is the most optimistic (even if blindly so, like Tiresias the blind prophet). For without such hope in the possibility of renewal and rebirth—as found in Eliot’s references to the Arthurian legend of the Fisher King and the biblical narrative of the risen Christ, both rooted in ancient fertility myths and rituals—what would be the point of continuing in such a bleak world if we did not cling to such myths that presupposed our own worth or even right to survive as a species? The Waste Land, like any myth or existential tragedy—such as Hamlet, which Eliot also heavily references—seeks to find meaning in a world that promises no meaning but only an inevitable march toward death and our common mortality. Depressing, indeed, yet Eliot at least manages to look ahead while also looking toward the past as a possible hope for regeneration and new life, as promised by the myths he is building from and using as the foundation for his text. For Eliot, whose burgeoning commitment to religious faith was growing at this time, all of these things are cyclical: with death comes rebirth, but only at the cost of sacrificing some representative member(s) of the community (a scapegoat, as René Girard argues in his work, namely, Violence and the Sacred).

Thus, Eliot finds some reassurance in religion and preserving the cultural past as an antidote (or palliative) for the present wreckage and perhaps as a cure for the future. Conversely, for Yeats, in his fear of what may come—represented by the beast “slouching toward Bethlehem” and all the other cyclical, spiraling imagery in his poem—it seems that we are spiraling toward our ultimate end, and I mean in apocalyptic terms, the End. This is kind of an odd thing, and perhaps does not qualify Yeats’ work as apocalyptic but rather purely dystopian. Let me explain. The tradition of apocalyptic literature or the apocalyptic imagination presupposes a cataclysmic break in time, which signifies a break with the past; however, this breaking of the old world is often represented as a good (albeit painful) occurrence so that a new world might come to be, free from all the death and decay and decadence inherent in millennial fears. And so, inherent in the End is the hope for a new beginning, or at least a fresh start, a clearing away of all the detritus and rubbish and waste of culture and history. The Apocalypse or End is of course a myth in itself, and an incredibly violent and problematic one that has continued to plague the 20th and 21st centuries in its imaginative fervor for a radical obliteration of what any one group, often fundamentalist, hopes to be rid of so that they may come to rule the new world order. After all, Revelations can be read as a revenge fantasy concocted by John of Patmos when he was imprisoned and improvising his grand, celestial plan of retribution against the Romans and those in power who were responsible for persecuting the new Christians. Nevertheless, Revelations is a very powerful revenge fantasy, as it continues to play out in our literature and cultural myths, as well as quite a few fundamentalist cults. We'll explore more fully this aspect of fundamentalist apocalyptic beliefs in Week 5.

Thus, Yeats, who in some ways views himself as a visionary prophet, seems to see only further destruction to come, or at least further darkness; all the old consolatory myths (such as those found in religion) cannot be relied upon to make sense of the new world order, since religion itself, as Yeats seems to imply, has been responsible for such cataclysmic events. At the same time, in “The Second Coming,” Yeats relies on the same biblical myth of apocalypse that he is critiquing in order to construct the terrain of his poem. For Eliot, the broken land and broken, hollow people who appear to be no more than walking corpses, trapped in the Underworld (of a devastated London), indicates a broken culture; rather, all the old fragments of culture—religion, myth, and literary tradition—are no longer sufficient or capable of providing sense and unity. Yet, much like Yeats and to a far greater extent, Eliot’s poem is constructed entirely of that broken culture, and as the primary speaker of the text claims, to “shore up these fragments against my ruin” might be the only way to salvage something and create something new. Because, in Eliot’s view, it is culture and all the art and “higher” thinking/forms of creation that humans are capable of which remain key to the survival of civilization in the face of such wide-scale destruction. Art and culture is what “civilizes” us, or so this seems to be the prayer that Eliot is offering, just as the poem ends in a prayer, “Shantih Shantih Shantih,” a plea for “the peace that passeth understanding.”

Granted, Eliot has been accused of elitism and cultural snobbery (not to mention racism and sexism), and nearly a hundred years after the publication of The Waste Land, we have yet to see if literature and art are capable of saving us from ourselves. I would like to believe there is some truth and value to Eliot’s fervent faith in culture as salvation/redemption (from our own brutal potential for violence, hatred, xenophobia, and destruction), though I’m probably far too influenced by a postmodernist or even posthumanist point of view to buy into the investment in such grand narratives or “truths” that Eliot would like to recover. I will give him credit, though, for being hopeful—and in my opinion, out of all the poems we’ve read this week, Eliot’s is the most optimistic (even if blindly so, like Tiresias the blind prophet). For without such hope in the possibility of renewal and rebirth—as found in Eliot’s references to the Arthurian legend of the Fisher King and the biblical narrative of the risen Christ, both rooted in ancient fertility myths and rituals—what would be the point of continuing in such a bleak world if we did not cling to such myths that presupposed our own worth or even right to survive as a species? The Waste Land, like any myth or existential tragedy—such as Hamlet, which Eliot also heavily references—seeks to find meaning in a world that promises no meaning but only an inevitable march toward death and our common mortality. Depressing, indeed, yet Eliot at least manages to look ahead while also looking toward the past as a possible hope for regeneration and new life, as promised by the myths he is building from and using as the foundation for his text. For Eliot, whose burgeoning commitment to religious faith was growing at this time, all of these things are cyclical: with death comes rebirth, but only at the cost of sacrificing some representative member(s) of the community (a scapegoat, as René Girard argues in his work, namely, Violence and the Sacred).

Thus, Eliot finds some reassurance in religion and preserving the cultural past as an antidote (or palliative) for the present wreckage and perhaps as a cure for the future. Conversely, for Yeats, in his fear of what may come—represented by the beast “slouching toward Bethlehem” and all the other cyclical, spiraling imagery in his poem—it seems that we are spiraling toward our ultimate end, and I mean in apocalyptic terms, the End. This is kind of an odd thing, and perhaps does not qualify Yeats’ work as apocalyptic but rather purely dystopian. Let me explain. The tradition of apocalyptic literature or the apocalyptic imagination presupposes a cataclysmic break in time, which signifies a break with the past; however, this breaking of the old world is often represented as a good (albeit painful) occurrence so that a new world might come to be, free from all the death and decay and decadence inherent in millennial fears. And so, inherent in the End is the hope for a new beginning, or at least a fresh start, a clearing away of all the detritus and rubbish and waste of culture and history. The Apocalypse or End is of course a myth in itself, and an incredibly violent and problematic one that has continued to plague the 20th and 21st centuries in its imaginative fervor for a radical obliteration of what any one group, often fundamentalist, hopes to be rid of so that they may come to rule the new world order. After all, Revelations can be read as a revenge fantasy concocted by John of Patmos when he was imprisoned and improvising his grand, celestial plan of retribution against the Romans and those in power who were responsible for persecuting the new Christians. Nevertheless, Revelations is a very powerful revenge fantasy, as it continues to play out in our literature and cultural myths, as well as quite a few fundamentalist cults. We'll explore more fully this aspect of fundamentalist apocalyptic beliefs in Week 5.

Dorothea Tanning, Notes for an Apocalypse, 1978, oil on canvas (https://www.dorotheatanning.org/)

Apocalyptic literature is one of my primary areas of scholarship, so I apologize for digressing into a lesson on the ideology and myths specific to the genre, but I think it’s useful to understand the contexts of apocalypse as a literary tradition in relation to this week’s readings. So, where am I going with this? Well, I would say, The Waste Land is in many ways a beautiful, maddening, at-war-with-itself, prime specimen of this genre that I think longs for that new beginning but fails to achieve it. “The Second Coming” is in many ways dismissive of the genre, and rightly so, expressing the fear that our clinging to such cyclical myths of violence and destruction and rebirth really only brings us more violence and death rather than new life. Yeats seems to suggest that we must create a new mythology, a new narrative that escapes Revelations and its threat of the Anti-Christ, a beast of terror and apathy that leads us nowhere. Yeats of course only leaves us with apprehension of the old myths and their continuing influence rather than any genuinely new redemptive myth, which brings me, finally, to Mina Loy. (NB: I also wrote a fictional biography of Loy so, admittedly, she is my favorite writer here in this grouping of texts.)

One of the things that I find fascinating about Loy’s “Songs to Joannes” is that it does not seem to make any overt, concrete cultural references. It’s as if the poem exists in a kind of cultural vacuum where references and allusions to any reality outside of the speaker’s own claustrophobic interior experiences seem to have no place of privilege or room for expression. Even while the speaker and the poem is intent on deconstructing all the old romantic myths and myths of romance with the aim of “sweeping the brood clear out,” I would actually say, as I have elsewhere (see my explication of “Songs to Joannes” provided in the Prezi) that her text is the most apocalyptic out of all those we’ve read this week. Loy has no sense of nostalgia for the old remnants of a world that has been shattered but embraces chaos and a truly new world, because perhaps in her view this is the only revolutionary path toward true liberation for women, and for a “purer,” more honest relationship between the sexes (see the additional Power Point intro to 20th Century Britain for further discussion of the perceived “war between the sexes” during and after WWI).

The patriarchal system is predicated on and sustains itself through a masculinist culture of war and aggression, as Virginia Woolf later argued in Three Guineas, published in 1938 right before the start of the Second World War. According to Woolf, patriarchy is perpetual war against all those it deems “Other” and Loy would happily eradicate such a system in search of a new one—and there are indeed beautiful moments in her poem when she tries to envision what that new world might look like, where “evolution falls foul of sexual difference.” Similar to Yeats, however, Loy fears that in spite of her own visionary longing for new myths/narratives or an “elsewhere” and an “other” reality that might be born/borne out of “the blood printed on a butterfly’s wings,” her poem still ends in despair, or cynicism. For it is “Love—the preeminent litterateur” that literally has the last word in the poem. In other words, regardless of Loy’s radical vision, the poem’s ending implies that the same myths (of love, romance, sexual discord and oppression) will continue to win out as long as we have “Pig Cupid snuffling his nose” and butting in to the affairs of anyone who attempts to discover “something new … something nascent … something that cannot be articulated.” Loy’s apocalyptic vision is for something quite radical: a new language and form of poetry that might reconcile rather than divide the sexes into separate, hostile spheres.

One of the things that I find fascinating about Loy’s “Songs to Joannes” is that it does not seem to make any overt, concrete cultural references. It’s as if the poem exists in a kind of cultural vacuum where references and allusions to any reality outside of the speaker’s own claustrophobic interior experiences seem to have no place of privilege or room for expression. Even while the speaker and the poem is intent on deconstructing all the old romantic myths and myths of romance with the aim of “sweeping the brood clear out,” I would actually say, as I have elsewhere (see my explication of “Songs to Joannes” provided in the Prezi) that her text is the most apocalyptic out of all those we’ve read this week. Loy has no sense of nostalgia for the old remnants of a world that has been shattered but embraces chaos and a truly new world, because perhaps in her view this is the only revolutionary path toward true liberation for women, and for a “purer,” more honest relationship between the sexes (see the additional Power Point intro to 20th Century Britain for further discussion of the perceived “war between the sexes” during and after WWI).

The patriarchal system is predicated on and sustains itself through a masculinist culture of war and aggression, as Virginia Woolf later argued in Three Guineas, published in 1938 right before the start of the Second World War. According to Woolf, patriarchy is perpetual war against all those it deems “Other” and Loy would happily eradicate such a system in search of a new one—and there are indeed beautiful moments in her poem when she tries to envision what that new world might look like, where “evolution falls foul of sexual difference.” Similar to Yeats, however, Loy fears that in spite of her own visionary longing for new myths/narratives or an “elsewhere” and an “other” reality that might be born/borne out of “the blood printed on a butterfly’s wings,” her poem still ends in despair, or cynicism. For it is “Love—the preeminent litterateur” that literally has the last word in the poem. In other words, regardless of Loy’s radical vision, the poem’s ending implies that the same myths (of love, romance, sexual discord and oppression) will continue to win out as long as we have “Pig Cupid snuffling his nose” and butting in to the affairs of anyone who attempts to discover “something new … something nascent … something that cannot be articulated.” Loy’s apocalyptic vision is for something quite radical: a new language and form of poetry that might reconcile rather than divide the sexes into separate, hostile spheres.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed