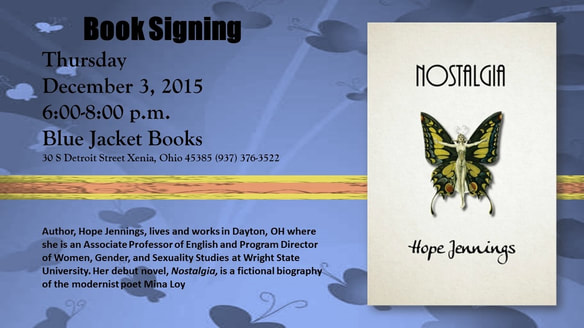

Nostalgia is the definitive biography of Mina Byrne, obscure avant-garde poet, painter, lamp-shade maker, and never-before-suspected muse of infamous Russian-American novelist, Vasili Novikov, and his son, Andrew Brennan, Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright. Over ten years in the making, Nostalgia draws from unpublished manuscripts, letters, and poems, reconstructing hypothetical paintings and lost photographs, reinventing forgotten eras, crisscrossing continents, and following its own laws of space and time. This groundbreaking portrait of an unknown and possibly plagiarized life presents a metafictional map of literary obsession, sexual betrayal, and monstrous megalomania. Traversing the landscape of a derelict past, we encounter schizophrenic sons, repressed philosophers, pugilist film stars, vampiric fathers, spectral butterflies, eccentric aunts, flamboyant flâneurs, reclusive mothers, bawdy vaudevillians, tittering dilettantes, absurd futurists, one of the most unromantic heroines imaginable, and much, much more...

Praise for Nostalgia

"Hope Jennings' always self-aware writing reminds me of my personal criteria for reading fiction—that it be entertaining, and that it be intellectually stimulating. Nostalgia hits the mark on both points. Jennings has created, in her fictional biography of Mina Loy, a captivating biopic that is as cinematic as it is poetic, as engaging to the imagination as a tumble down the rabbit hole."

~ CYNTHIA REESER, editor-in-chief of Prick of the Spindle, publisher of Aqueous Books, and author of Light and Trials of Light

CHAPTER ONE: A Prodigal Daughter

Mina’s sixty-eighth year began and ended the night she slipped out into a winter storm, and I can only imagine why she felt compelled to go wandering in the middle of the night in the middle of a snowfall. Perhaps she’d been awakened from a dream, in which she roamed, forever ageless, through a grove of blossoming tulip poplars. A man she’d once loved and lost led her by the hand, black pearls dripping from the ocean of his eyes. Butterflies chased stars through her hair and a small beloved child ran laughing before them in a field of crimson poppies, tainted only by the slanting shadows of a sun setting on a horizon that could never be reached.

The dream disintegrated in the emptiness of Mina’s bedroom when a phone rang and forced her out of sleep. She sat up, groping for the receiver, only to be confronted with one brief familiar husky hello and then silence. She breathed into the crackling static of collapsed time, waiting to continue a conversation that had been severed too soon, too long ago. When the mechanical, automated voice broke in, advising her to try that number again, she set the receiver down on the bedside table, abandoning it off the hook. Disorientated, Mina stumbled barefoot down the moonlit corridor of her hall, intending to calm her nerves with a late night snack or a cup of the bitter, black coffee she loved. Instead, she discovered an unexpected visitor sitting at her kitchen table, the unruly ghost of a man smiling recklessly, challenging her with a sly tilt of his dark head to follow him outside into the wintry unexpected landscape of his return.

Determined not to lose sight of him this time, Mina vacated her premises, leaving the front door ajar and a small drift of snow to sweep across its threshold. Once Mina caught up to him, where he stood beneath the looming skeleton of a tulip poplar that no longer existed except in her memory, she allowed him to take her hand and twirl her through the silent swirling snow descending from the bright star-strewn sky. Revolving in each other’s arms to the swooping dives and swelling, anguished notes of O mio babbino caro, Mina was transported to a late summer evening when she’d waltzed barefoot along the sloping lawn of a Tuscan villa, impossibly happy despite the knowledge that she would vanish, abandoning him in the morning. Forgiven now, after so many years (for why else had he come back to her?), she smiled up into the vast infinity of stars and falling snow, as she spun further into the past, sinking finally to the ground where she lay trapped in the blinding glare of the headlamps of a passing vehicle as it cautiously made its way down the winding mountain road adjacent to Mina’s property.

The driver was fortunately a level-headed local; he wrapped her in a spare blanket stored away in the trunk of his car, brought her to the hospital, and supplied the overnight nurse with a name, which helped her track down the number to call in the event of emergency. That number went unanswered and Mina was filed away under the general category of elderly woman whose sanity had cracked and split open from the burden of a life outlived. Nevertheless, the nurse dutifully paused on her rounds to check her patient’s fading vital signs and was later able to report, mildly perplexed, that in Mina’s last moments she had mumbled repeatedly, feverishly, that she knew where she was going, she knew how to find her way, and at last, slipping into sleep, murmuring, it’s through the looking glass…

On the other side of that glass, Mina returns to the memory of her childhood. Exiled to the sprawling overgrown garden pocketed behind the Devonshire cottage in which she was born, she lies down on her back, sinking into the springy bed of unmown lawn, eyes closed, and summoning sufficient courage to gaze unflinchingly into the sun. Her mother has informed her, most likely during one of their abbreviated bedtime stories, that if she looks directly into that scorching ball of flame, her vision will become terribly damaged; she may even suffer incurable blindness. When Mina musters the courage to open her eyes, there is no flash of lightning, no bolt of retribution, only a murky overcast haze. She longs for the day when she might run away to a warmer, sunnier place where it never rains, and resentfully studies the clouds, fashioning grotesque shapes out of their pliable, evaporating bodies. She thinks she is dreaming, or that she has, in fact, been blessed by a message from some inarticulate god, when a small tear in the oppressive blanket of cumuli frays into a transparent, ragged hole. A gigantic eye opens onto the world below, and streaming from its blue pupil, the sun tumbles down through the sky as evidence of its existence, as blazing tribute to her presence. She wants to cry, but decides otherwise, rising from the crumpled lawn and disdainfully brushing aside the crushed blades of grass clinging to her behind.

Tiptoeing into the empty kitchen, she is aware of having been transformed into a new creature, which she must keep secret from the arrogant disregard of her father and the eccentric inscrutability of her mother. If she told them, they would translate her vision into something they could possess for themselves. She slowly chews a slice of toasted pumpernickel smeared with marmalade, and listens to the impersonal clacking of her father’s typewriter in the study down the hall. From above, she detects the whirling leaps and thumping descents of her mother rehearsing a bizarre contorted dance no one will ever have the privilege of seeing. She does not try to decipher the meaning of her vision, but is certain she has been singled out for some life-long sacred mission. She considers briefly Jeanne d’Arc, and though she accepts that she too may be sentenced to a tediously misunderstood and ostracized fate, she will refuse anyone the opportunity of burning her at the stake. She will grow up to be quite unlike any woman who has ever lived before; for now, though, she softly hums along to the internal rhyme and rhythm of the continuously stitching fabric of her flesh and rapidly evolving marrow of her bones.

The following Sunday in church she sits beside her mother in the front pew, listening listlessly to the droning of her father’s sermon, which is a flawlessly structured homily on the possibilities and limitations of man’s transcendence. He should have remained a tutor in philosophy at Cambridge, since he obviously begrudges his economically imposed decision to tend this bleating flock of irreligious country folk, before whom he squanders his gleaming pearls of wisdom. They’d much rather receive booming tirades and terrifying bombardments, the spectacle of eternal hell, fire and brimstone wreaked upon the exiled and wicked children of this earth, who have been cast out of paradise by a merciless and vengeful god who is our father who may or may not be in heaven. Turning to his wife as their example, they belligerently yawn, glance impatiently at their fellow congregants, skim distractedly through the hymnal, and are equally resentful towards the social obligation of attending Sunday service.

Not one of them appreciates the reverend’s measured, atonal voice reasoning quite uselessly on the benefits of considering their metaphysical aspirations. They are confused by that word, metaphysical, leading each and every one of them to the conclusion that he is mocking their ignorance, which, admittedly, he is. She, however, adores her father, and decides her metaphysical aspiration might someday be to exceed his pure embodiment of pure intellect. Such a lofty goal has the discouraging effect of making her feel a very lowly earth-bound creature; the usual Sunday ennui tempts her into disregarding, along with everyone else, her father’s vain exhortations to strive beyond all physical desires.

Averting her gaze, she locates the image of the stained glass window just directly above and to the left of her father’s receding hairline. The virgin mother sits where she always sits, holding the wizened infant in her lap, the same two self-satisfied incipient smiles glazed onto their stiff lips. The archangel Gabriel hovers over them, observing mother and child with an equally smug rather too-human grin. They all look so happy with themselves, this ludicrous trinity. Happiness like that simply cannot exist, she muses, even if you are a winged messenger of God or God’s singular child or that child’s sanctified mother. Perhaps this is a delusion of happiness that can only be gained through spiritual aspirations, or perhaps this is the aspiration we must transcend. Mina would have continued ruminating on these conundrums, but the sun crashes into the stained glass, splintering the image into a thousand prisms of colored light. Kaleidoscopic shards scatter across her pale upturned face, and the carefully constructed mosaic of cut glass, illuminated by the sun, miraculously shifts so that the dumb lifeless smiles of mother, child, and angel are transformed, distorted but now beautiful, believable, promising the infinite possibilities of art and nature in perfect union with each other.

In that moment of comprehension, the beatific smile Mina offers her father causes him to lose his place, allowing for a distracted pause that prompts the congregation to break out into a lusty rendition of the closing hymn. Her mother also observes her daughter’s beamish grin and generously mirrors the smile. Together, they leap at the opportunity to raise their voices in song, blessedly bringing to an end her father’s tortuous speech. After the final resonating amen, Lauren stoops to whisper into her child’s ear: “Mina, my love, you must never forget.” It is never explained, however, exactly what she should remember; and Mina never once thought to ask.

Shortly after Mina’s death I discovered a box of several unfinished manuscripts that she had left for me, none of them dated as to when they’d been written, but once carefully sorted they provide a rough chronology of Mina’s life. The first of these manuscripts, Laman Duare (the eponymous title of the text’s heroine and clearly an anagram of Mina’s parent’s first names), presents a fragmented narrative that nevertheless allows for an overall impression of her childhood. Mina’s representation of this, however, was perhaps as distorted as that stained-glass window, a scene borrowed from Laman Duare’s recollections and inserted above with some of my own revisions to indicate that this episode more accurately belongs to Mina’s own life.

Although this might seem a dishonest move on my part or even a clumsy attempt to turn fiction into fact, if one did not know anything about Mina, then the literate reader of Laman Duare, upon opening its first pages (if it ever gets published), would immediately suspect its narrator’s memories to be thinly plagiarized from another novel (and admittedly a more masterfully written novel). The reader could hardly be at fault for this hasty assumption, since we are told right away that just when Laman, a bohemian artist living in Paris, is feeling securely free from all ties to the past, she is forced to attend some insipid soirée hosted by one of her fellow expatriates where she is offered a cup of unsweetened Earl Grey, and with one sip of its milky bitterness, she is transported to the claustrophobic landscape of her English childhood. There she revisits the uneventful experience of growing up in a home where all dreams and desires have been stifled, yet where love is the ghost haunting that home’s inhabitants; and here is where the narrative diverges from familiar terrain, at least for our assumed reader.

For those of us who are familiar with Mina’s biography (which admittedly is an obscure text since it has yet to be written, though I am obviously at this very moment in the process of writing it), we might be justified in substituting Laman’s depiction of her childhood for Mina’s formative years while also saving Mina from the accusation of shamelessly stealing from another author’s memories. As such, the impossibly messy manuscript of Laman Duare might be salvaged and rewritten here as the first chapter of Mina’s biography (though admittedly I must steal from Mina’s memories in order to write anything that unearths her earliest years, including her origins, of which she never spoke, as far as I know).

As revealed, then, in the manuscript of Laman Duare, Mina’s father, the Rev. Adam Byrne, was of grubby Anglo-Irish stock; against all economic disadvantages, he had succeeded in winning a place at Cambridge where after three years of endearing himself to the more eminent dons of his college, he was assured of a small but coveted parish within St. Albans. He then made the ill-considered choice of marrying the daughter of a Hungarian-Jewish investment banker, whose father had been an importer of exotic fabrics, and his father before that a successful draper. Lauren Lowell had enjoyed all the advantages of a pampered childhood. For the past three generations since immigrating to the beating heart of Empire, the Lowells had accumulated enough wealth to have become one of the more affluent and respected Jewish households that had managed to escape their grubby East End origins. The Cambridge dons and Lowell patriarchs, however, were in harmonious agreement that there could be no earthly advantage to such an interracial, never mind interfaith, alliance. It was the popular belief of their time that the miscegenation of Gentile and Hebrew would only lead to a mongrelized nation of children poorly-suited to recognizing their proper place within the British scheme of things.

Forced to take a living beneath his ambitions, and disowned by her family, Mina’s parents found themselves exiled to the intellectual and social backwater of rural Devon. Lauren made an initial good-faith gesture of converting to the Anglican Church, then promptly disengaged from all communal activities of charity, tea-hosting, and hypocrisy expected of a vicar’s wife. The insulated, sophisticated world of Lauren’s London upbringing had not prepared her for the ignorance of the ruddy-faced, coarse wives of the local farmers, whose grumbling whispers conjecturing over the mystery of her exotic dark looks and stilted mannerisms were maliciously intended to be overheard. By the time Mina was born, within the first year of her parent’s marriage, Lauren had stopped leaving the house altogether. Her only concession was to attend the required weekly appearance at her husband’s Sunday sermon where she would give such a studied performance of disinterested resentment that her presence did not in any way inspire further affection towards her from either the vicar or his parishioners. By the time Mina began toddling about on her own, no longer requiring the sustained attentions of her mother, Lauren and Adam Byrne no longer shared a bed, or even the same existence.

In all the years of her unconventional upbringing, throughout which the members of the Byrne household held no sustained contact with each other, or any society outside the vicarage’s inner walls and unspoken rules, Mina took for granted her family’s peculiarly estranged cohabitation. She thought this was how all families endured each other’s enforced presence. There was, after all, no visible proof that her parents had once been passionately in love before they had wildly, unadvisedly married against all better judgments, and then discovered love was not enough to sustain them in the face of overwhelming social and familial disapproval.

Mina was left to spend her days wandering in and out of the cramped rooms of the vicarage, seeking in each of them proof of her parent’s presence, only to discover they were always located in some other part of the house, behind closed doors and in chambers Mina was never allowed to enter. She sniffed out the fading perfume or whiff of pipe smoke her parents left as traces of themselves; she listened to footsteps pacing along hallways, a typewriter tapping away in communication with itself, a gramophone repeatedly scratching over the same grooves of a finished record no one bothered to lift and turn over. Often, the sound of her mother singing an old Hungarian lullaby drifted down the long passageway separating Mina’s bedroom from Lauren’s locked room; or, the dry, emotionless voice of her father offering unwanted advice to one of his begrudging flock could be overheard when Mina pressed her ear to the door of his study. Whenever she did come into contact with her parents, it was always on opposite ends of the day and never with both of them together.

Her father, who had taken Mina’s education upon himself, set aside several hours of every morning to meet with his daughter. The first lessons began when she was three, and as soon as the rudiments of reading were accomplished Mina was expected to master a more demanding set of ABCs. After proving a diligent student of Aeschylus, Boethius, and Cicero, she was rewarded with Augustine’s Confessions, or the Letters of Abelard and Héloise. Although Adam expurgated the racier bits, for the most part he was not very attentive, so Mina also became acquainted with the tales of Scheherazade and Shakespeare, the metaphysical wit of Donne and the rambunctious digressions of Sterne. If these liberal borrowings from her father’s library were discovered, then as long as she could demonstrate an intellectual response to her illicit choice of reading, Adam decided he had no reasonable justification for further censoring his daughter’s education.

As for Mina’s minimal contact with her mother, this usually took place on those evenings when Lauren remembered to visit her daughter’s bedside. She would do so with the intention of bestowing upon Mina a bedtime story, something Lauren vaguely felt was a maternal obligation, yet discovered herself incapable of providing without some kind of preparation or assistance. Mina was thus left to spend her unsupervised afternoons daydreaming in the privacy of the neglected garden while Lauren sat at her desk in her bedroom trying to think up some fabulous story that she might write down and then read aloud to her daughter at the close of yet another dull, empty day. When her imagination failed her, she attempted to compile into a journal various nuggets of wisdom that she believed, or rather guessed, every mother should pass down to her daughter. In the end, the most Lauren ever managed was a distracted kiss on the brow and sometimes, in her husky voice, a few inaudible phrases concerning the weather or the roses or the nesting sparrows or any other mundane, momentary thought that flitted through her head.

Eventually she gave up trying to speak to Mina. Some maternal mechanism had miserably malfunctioned, though Lauren persisted in her need to communicate the profound love she felt for her child yet was incapable of articulating. She began perusing lists of books from a mail-order catalogue, carefully dissecting their titles and abstracts to discern which ones might allow for a more meaningful dialogue with her daughter. She knew the girl was mad about books. Whenever Lauren accidentally entered a room where she did not expect to discover Mina, her daughter was usually sprawled out on the floor with several books keeping her company; thus Lauren had decided books were the way forward. It took several months to make her tortured selection, and when she finally gave Mina the seven-part set of A Child’s Progress, or, the Trials, Tribulations, and Triumphs of Bertram Benson, a popular series of children’s stories by the esteemed Mrs. Fiona Beresford, Mina accepted the gift with feigned gratitude, disdainfully frowning down at the gold-embossed title of the first volume, Bertram and the Goblet of Temptation. Lauren was devastated, and swore never to make a similar effort again.

Lauren, however, had not read the Bertram saga, and because she had no idea that its aim was to indoctrinate every good little boy and girl into becoming upstanding, moral Christians, advising them in patronizing tones how to tell the difference between right and wrong, how to honor their mothers and fathers, and always obediently, meekly turn the other cheek, she had no idea how offensive these books might be to her daughter, who’d already learned such lessons from reading The Oresteia. Lauren also never knew that as soon as she left the room, Mina did not cast the books aside but gulped down the entire Goblet of Temptation in a single night, drunkenly thrilled by the epic adventures of that sniveling Bertram Benson. It was the first time Mina had been allowed to participate in a character’s adventures for the purely vicarious pleasure of sharing in his perils and downfalls, his battles and victories, and without the portending doom of failing her father’s examination of her intellectual growth.

Of course, Mina could not help inwardly cringing at Mrs. Beresford’s stilted prose, or heartlessly critiquing the convoluted plot. Bertram’s advancement into adolescence and its accompanying picaresque sequence of ludicrous traps and snares was inanely improbable and little Bertie a silly, dim-sighted, and annoyingly priggish public school-boy who inspired very little sympathy in the reader (likely an unintended flaw on the part of Mrs. Beresford since each book’s dedication identified the author’s son, Billy Beresford, as her inspiration). Mina had no other childhood friends, and so she was inevitably as fascinated by Bertram as she was repulsed, and compulsively reread the Bertie books countless times over the course of countless nights in the privacy of her bedroom after her mother had kissed her goodnight.

She became Bertie’s greatest antagonist, playing out the many nefarious roles of villains who stood in the way of his moral progress: the Witch of Wolves; the Mage of Maleficent Mire; the Horrible Harpy, responsible for most of the hapless boy’s trials and tribulations; the slithering Melusine, who shape-shifted from an emerald-scaled sea-serpent into a green-eyed temptress (though Bertie inadvertently managed to triumph over her when he barged in on one of her clandestine baths, a dirty trick if there ever was one); and lastly, the most wicked of them all, the monstrous Lilith, who gave birth to demons and dragons, and haunted Bertie’s nightmares until he took some sleeping potion that made him nearly comatose. Mina began to think she existed in this fantastical world more fully than Bertie himself, and to the point where she stopped reading the books entirely. Instead, the lights remained turned down, and with the room descended into a blank darkness, Mina projected into its void an epic adventure of her own making. Bertie was quickly written out of the story, as he so rightly deserved. Mina now became the heroine, who thanks to her wits and beauty, her bravery and wisdom, rarely suffered a tribulation and always, in the end, triumphed…

© Hope Jennings, Nostalgia (Anti-Oedipus Press, 2015).

Mina’s sixty-eighth year began and ended the night she slipped out into a winter storm, and I can only imagine why she felt compelled to go wandering in the middle of the night in the middle of a snowfall. Perhaps she’d been awakened from a dream, in which she roamed, forever ageless, through a grove of blossoming tulip poplars. A man she’d once loved and lost led her by the hand, black pearls dripping from the ocean of his eyes. Butterflies chased stars through her hair and a small beloved child ran laughing before them in a field of crimson poppies, tainted only by the slanting shadows of a sun setting on a horizon that could never be reached.

The dream disintegrated in the emptiness of Mina’s bedroom when a phone rang and forced her out of sleep. She sat up, groping for the receiver, only to be confronted with one brief familiar husky hello and then silence. She breathed into the crackling static of collapsed time, waiting to continue a conversation that had been severed too soon, too long ago. When the mechanical, automated voice broke in, advising her to try that number again, she set the receiver down on the bedside table, abandoning it off the hook. Disorientated, Mina stumbled barefoot down the moonlit corridor of her hall, intending to calm her nerves with a late night snack or a cup of the bitter, black coffee she loved. Instead, she discovered an unexpected visitor sitting at her kitchen table, the unruly ghost of a man smiling recklessly, challenging her with a sly tilt of his dark head to follow him outside into the wintry unexpected landscape of his return.

Determined not to lose sight of him this time, Mina vacated her premises, leaving the front door ajar and a small drift of snow to sweep across its threshold. Once Mina caught up to him, where he stood beneath the looming skeleton of a tulip poplar that no longer existed except in her memory, she allowed him to take her hand and twirl her through the silent swirling snow descending from the bright star-strewn sky. Revolving in each other’s arms to the swooping dives and swelling, anguished notes of O mio babbino caro, Mina was transported to a late summer evening when she’d waltzed barefoot along the sloping lawn of a Tuscan villa, impossibly happy despite the knowledge that she would vanish, abandoning him in the morning. Forgiven now, after so many years (for why else had he come back to her?), she smiled up into the vast infinity of stars and falling snow, as she spun further into the past, sinking finally to the ground where she lay trapped in the blinding glare of the headlamps of a passing vehicle as it cautiously made its way down the winding mountain road adjacent to Mina’s property.

The driver was fortunately a level-headed local; he wrapped her in a spare blanket stored away in the trunk of his car, brought her to the hospital, and supplied the overnight nurse with a name, which helped her track down the number to call in the event of emergency. That number went unanswered and Mina was filed away under the general category of elderly woman whose sanity had cracked and split open from the burden of a life outlived. Nevertheless, the nurse dutifully paused on her rounds to check her patient’s fading vital signs and was later able to report, mildly perplexed, that in Mina’s last moments she had mumbled repeatedly, feverishly, that she knew where she was going, she knew how to find her way, and at last, slipping into sleep, murmuring, it’s through the looking glass…

On the other side of that glass, Mina returns to the memory of her childhood. Exiled to the sprawling overgrown garden pocketed behind the Devonshire cottage in which she was born, she lies down on her back, sinking into the springy bed of unmown lawn, eyes closed, and summoning sufficient courage to gaze unflinchingly into the sun. Her mother has informed her, most likely during one of their abbreviated bedtime stories, that if she looks directly into that scorching ball of flame, her vision will become terribly damaged; she may even suffer incurable blindness. When Mina musters the courage to open her eyes, there is no flash of lightning, no bolt of retribution, only a murky overcast haze. She longs for the day when she might run away to a warmer, sunnier place where it never rains, and resentfully studies the clouds, fashioning grotesque shapes out of their pliable, evaporating bodies. She thinks she is dreaming, or that she has, in fact, been blessed by a message from some inarticulate god, when a small tear in the oppressive blanket of cumuli frays into a transparent, ragged hole. A gigantic eye opens onto the world below, and streaming from its blue pupil, the sun tumbles down through the sky as evidence of its existence, as blazing tribute to her presence. She wants to cry, but decides otherwise, rising from the crumpled lawn and disdainfully brushing aside the crushed blades of grass clinging to her behind.

Tiptoeing into the empty kitchen, she is aware of having been transformed into a new creature, which she must keep secret from the arrogant disregard of her father and the eccentric inscrutability of her mother. If she told them, they would translate her vision into something they could possess for themselves. She slowly chews a slice of toasted pumpernickel smeared with marmalade, and listens to the impersonal clacking of her father’s typewriter in the study down the hall. From above, she detects the whirling leaps and thumping descents of her mother rehearsing a bizarre contorted dance no one will ever have the privilege of seeing. She does not try to decipher the meaning of her vision, but is certain she has been singled out for some life-long sacred mission. She considers briefly Jeanne d’Arc, and though she accepts that she too may be sentenced to a tediously misunderstood and ostracized fate, she will refuse anyone the opportunity of burning her at the stake. She will grow up to be quite unlike any woman who has ever lived before; for now, though, she softly hums along to the internal rhyme and rhythm of the continuously stitching fabric of her flesh and rapidly evolving marrow of her bones.

The following Sunday in church she sits beside her mother in the front pew, listening listlessly to the droning of her father’s sermon, which is a flawlessly structured homily on the possibilities and limitations of man’s transcendence. He should have remained a tutor in philosophy at Cambridge, since he obviously begrudges his economically imposed decision to tend this bleating flock of irreligious country folk, before whom he squanders his gleaming pearls of wisdom. They’d much rather receive booming tirades and terrifying bombardments, the spectacle of eternal hell, fire and brimstone wreaked upon the exiled and wicked children of this earth, who have been cast out of paradise by a merciless and vengeful god who is our father who may or may not be in heaven. Turning to his wife as their example, they belligerently yawn, glance impatiently at their fellow congregants, skim distractedly through the hymnal, and are equally resentful towards the social obligation of attending Sunday service.

Not one of them appreciates the reverend’s measured, atonal voice reasoning quite uselessly on the benefits of considering their metaphysical aspirations. They are confused by that word, metaphysical, leading each and every one of them to the conclusion that he is mocking their ignorance, which, admittedly, he is. She, however, adores her father, and decides her metaphysical aspiration might someday be to exceed his pure embodiment of pure intellect. Such a lofty goal has the discouraging effect of making her feel a very lowly earth-bound creature; the usual Sunday ennui tempts her into disregarding, along with everyone else, her father’s vain exhortations to strive beyond all physical desires.

Averting her gaze, she locates the image of the stained glass window just directly above and to the left of her father’s receding hairline. The virgin mother sits where she always sits, holding the wizened infant in her lap, the same two self-satisfied incipient smiles glazed onto their stiff lips. The archangel Gabriel hovers over them, observing mother and child with an equally smug rather too-human grin. They all look so happy with themselves, this ludicrous trinity. Happiness like that simply cannot exist, she muses, even if you are a winged messenger of God or God’s singular child or that child’s sanctified mother. Perhaps this is a delusion of happiness that can only be gained through spiritual aspirations, or perhaps this is the aspiration we must transcend. Mina would have continued ruminating on these conundrums, but the sun crashes into the stained glass, splintering the image into a thousand prisms of colored light. Kaleidoscopic shards scatter across her pale upturned face, and the carefully constructed mosaic of cut glass, illuminated by the sun, miraculously shifts so that the dumb lifeless smiles of mother, child, and angel are transformed, distorted but now beautiful, believable, promising the infinite possibilities of art and nature in perfect union with each other.

In that moment of comprehension, the beatific smile Mina offers her father causes him to lose his place, allowing for a distracted pause that prompts the congregation to break out into a lusty rendition of the closing hymn. Her mother also observes her daughter’s beamish grin and generously mirrors the smile. Together, they leap at the opportunity to raise their voices in song, blessedly bringing to an end her father’s tortuous speech. After the final resonating amen, Lauren stoops to whisper into her child’s ear: “Mina, my love, you must never forget.” It is never explained, however, exactly what she should remember; and Mina never once thought to ask.

Shortly after Mina’s death I discovered a box of several unfinished manuscripts that she had left for me, none of them dated as to when they’d been written, but once carefully sorted they provide a rough chronology of Mina’s life. The first of these manuscripts, Laman Duare (the eponymous title of the text’s heroine and clearly an anagram of Mina’s parent’s first names), presents a fragmented narrative that nevertheless allows for an overall impression of her childhood. Mina’s representation of this, however, was perhaps as distorted as that stained-glass window, a scene borrowed from Laman Duare’s recollections and inserted above with some of my own revisions to indicate that this episode more accurately belongs to Mina’s own life.

Although this might seem a dishonest move on my part or even a clumsy attempt to turn fiction into fact, if one did not know anything about Mina, then the literate reader of Laman Duare, upon opening its first pages (if it ever gets published), would immediately suspect its narrator’s memories to be thinly plagiarized from another novel (and admittedly a more masterfully written novel). The reader could hardly be at fault for this hasty assumption, since we are told right away that just when Laman, a bohemian artist living in Paris, is feeling securely free from all ties to the past, she is forced to attend some insipid soirée hosted by one of her fellow expatriates where she is offered a cup of unsweetened Earl Grey, and with one sip of its milky bitterness, she is transported to the claustrophobic landscape of her English childhood. There she revisits the uneventful experience of growing up in a home where all dreams and desires have been stifled, yet where love is the ghost haunting that home’s inhabitants; and here is where the narrative diverges from familiar terrain, at least for our assumed reader.

For those of us who are familiar with Mina’s biography (which admittedly is an obscure text since it has yet to be written, though I am obviously at this very moment in the process of writing it), we might be justified in substituting Laman’s depiction of her childhood for Mina’s formative years while also saving Mina from the accusation of shamelessly stealing from another author’s memories. As such, the impossibly messy manuscript of Laman Duare might be salvaged and rewritten here as the first chapter of Mina’s biography (though admittedly I must steal from Mina’s memories in order to write anything that unearths her earliest years, including her origins, of which she never spoke, as far as I know).

As revealed, then, in the manuscript of Laman Duare, Mina’s father, the Rev. Adam Byrne, was of grubby Anglo-Irish stock; against all economic disadvantages, he had succeeded in winning a place at Cambridge where after three years of endearing himself to the more eminent dons of his college, he was assured of a small but coveted parish within St. Albans. He then made the ill-considered choice of marrying the daughter of a Hungarian-Jewish investment banker, whose father had been an importer of exotic fabrics, and his father before that a successful draper. Lauren Lowell had enjoyed all the advantages of a pampered childhood. For the past three generations since immigrating to the beating heart of Empire, the Lowells had accumulated enough wealth to have become one of the more affluent and respected Jewish households that had managed to escape their grubby East End origins. The Cambridge dons and Lowell patriarchs, however, were in harmonious agreement that there could be no earthly advantage to such an interracial, never mind interfaith, alliance. It was the popular belief of their time that the miscegenation of Gentile and Hebrew would only lead to a mongrelized nation of children poorly-suited to recognizing their proper place within the British scheme of things.

Forced to take a living beneath his ambitions, and disowned by her family, Mina’s parents found themselves exiled to the intellectual and social backwater of rural Devon. Lauren made an initial good-faith gesture of converting to the Anglican Church, then promptly disengaged from all communal activities of charity, tea-hosting, and hypocrisy expected of a vicar’s wife. The insulated, sophisticated world of Lauren’s London upbringing had not prepared her for the ignorance of the ruddy-faced, coarse wives of the local farmers, whose grumbling whispers conjecturing over the mystery of her exotic dark looks and stilted mannerisms were maliciously intended to be overheard. By the time Mina was born, within the first year of her parent’s marriage, Lauren had stopped leaving the house altogether. Her only concession was to attend the required weekly appearance at her husband’s Sunday sermon where she would give such a studied performance of disinterested resentment that her presence did not in any way inspire further affection towards her from either the vicar or his parishioners. By the time Mina began toddling about on her own, no longer requiring the sustained attentions of her mother, Lauren and Adam Byrne no longer shared a bed, or even the same existence.

In all the years of her unconventional upbringing, throughout which the members of the Byrne household held no sustained contact with each other, or any society outside the vicarage’s inner walls and unspoken rules, Mina took for granted her family’s peculiarly estranged cohabitation. She thought this was how all families endured each other’s enforced presence. There was, after all, no visible proof that her parents had once been passionately in love before they had wildly, unadvisedly married against all better judgments, and then discovered love was not enough to sustain them in the face of overwhelming social and familial disapproval.

Mina was left to spend her days wandering in and out of the cramped rooms of the vicarage, seeking in each of them proof of her parent’s presence, only to discover they were always located in some other part of the house, behind closed doors and in chambers Mina was never allowed to enter. She sniffed out the fading perfume or whiff of pipe smoke her parents left as traces of themselves; she listened to footsteps pacing along hallways, a typewriter tapping away in communication with itself, a gramophone repeatedly scratching over the same grooves of a finished record no one bothered to lift and turn over. Often, the sound of her mother singing an old Hungarian lullaby drifted down the long passageway separating Mina’s bedroom from Lauren’s locked room; or, the dry, emotionless voice of her father offering unwanted advice to one of his begrudging flock could be overheard when Mina pressed her ear to the door of his study. Whenever she did come into contact with her parents, it was always on opposite ends of the day and never with both of them together.

Her father, who had taken Mina’s education upon himself, set aside several hours of every morning to meet with his daughter. The first lessons began when she was three, and as soon as the rudiments of reading were accomplished Mina was expected to master a more demanding set of ABCs. After proving a diligent student of Aeschylus, Boethius, and Cicero, she was rewarded with Augustine’s Confessions, or the Letters of Abelard and Héloise. Although Adam expurgated the racier bits, for the most part he was not very attentive, so Mina also became acquainted with the tales of Scheherazade and Shakespeare, the metaphysical wit of Donne and the rambunctious digressions of Sterne. If these liberal borrowings from her father’s library were discovered, then as long as she could demonstrate an intellectual response to her illicit choice of reading, Adam decided he had no reasonable justification for further censoring his daughter’s education.

As for Mina’s minimal contact with her mother, this usually took place on those evenings when Lauren remembered to visit her daughter’s bedside. She would do so with the intention of bestowing upon Mina a bedtime story, something Lauren vaguely felt was a maternal obligation, yet discovered herself incapable of providing without some kind of preparation or assistance. Mina was thus left to spend her unsupervised afternoons daydreaming in the privacy of the neglected garden while Lauren sat at her desk in her bedroom trying to think up some fabulous story that she might write down and then read aloud to her daughter at the close of yet another dull, empty day. When her imagination failed her, she attempted to compile into a journal various nuggets of wisdom that she believed, or rather guessed, every mother should pass down to her daughter. In the end, the most Lauren ever managed was a distracted kiss on the brow and sometimes, in her husky voice, a few inaudible phrases concerning the weather or the roses or the nesting sparrows or any other mundane, momentary thought that flitted through her head.

Eventually she gave up trying to speak to Mina. Some maternal mechanism had miserably malfunctioned, though Lauren persisted in her need to communicate the profound love she felt for her child yet was incapable of articulating. She began perusing lists of books from a mail-order catalogue, carefully dissecting their titles and abstracts to discern which ones might allow for a more meaningful dialogue with her daughter. She knew the girl was mad about books. Whenever Lauren accidentally entered a room where she did not expect to discover Mina, her daughter was usually sprawled out on the floor with several books keeping her company; thus Lauren had decided books were the way forward. It took several months to make her tortured selection, and when she finally gave Mina the seven-part set of A Child’s Progress, or, the Trials, Tribulations, and Triumphs of Bertram Benson, a popular series of children’s stories by the esteemed Mrs. Fiona Beresford, Mina accepted the gift with feigned gratitude, disdainfully frowning down at the gold-embossed title of the first volume, Bertram and the Goblet of Temptation. Lauren was devastated, and swore never to make a similar effort again.

Lauren, however, had not read the Bertram saga, and because she had no idea that its aim was to indoctrinate every good little boy and girl into becoming upstanding, moral Christians, advising them in patronizing tones how to tell the difference between right and wrong, how to honor their mothers and fathers, and always obediently, meekly turn the other cheek, she had no idea how offensive these books might be to her daughter, who’d already learned such lessons from reading The Oresteia. Lauren also never knew that as soon as she left the room, Mina did not cast the books aside but gulped down the entire Goblet of Temptation in a single night, drunkenly thrilled by the epic adventures of that sniveling Bertram Benson. It was the first time Mina had been allowed to participate in a character’s adventures for the purely vicarious pleasure of sharing in his perils and downfalls, his battles and victories, and without the portending doom of failing her father’s examination of her intellectual growth.

Of course, Mina could not help inwardly cringing at Mrs. Beresford’s stilted prose, or heartlessly critiquing the convoluted plot. Bertram’s advancement into adolescence and its accompanying picaresque sequence of ludicrous traps and snares was inanely improbable and little Bertie a silly, dim-sighted, and annoyingly priggish public school-boy who inspired very little sympathy in the reader (likely an unintended flaw on the part of Mrs. Beresford since each book’s dedication identified the author’s son, Billy Beresford, as her inspiration). Mina had no other childhood friends, and so she was inevitably as fascinated by Bertram as she was repulsed, and compulsively reread the Bertie books countless times over the course of countless nights in the privacy of her bedroom after her mother had kissed her goodnight.

She became Bertie’s greatest antagonist, playing out the many nefarious roles of villains who stood in the way of his moral progress: the Witch of Wolves; the Mage of Maleficent Mire; the Horrible Harpy, responsible for most of the hapless boy’s trials and tribulations; the slithering Melusine, who shape-shifted from an emerald-scaled sea-serpent into a green-eyed temptress (though Bertie inadvertently managed to triumph over her when he barged in on one of her clandestine baths, a dirty trick if there ever was one); and lastly, the most wicked of them all, the monstrous Lilith, who gave birth to demons and dragons, and haunted Bertie’s nightmares until he took some sleeping potion that made him nearly comatose. Mina began to think she existed in this fantastical world more fully than Bertie himself, and to the point where she stopped reading the books entirely. Instead, the lights remained turned down, and with the room descended into a blank darkness, Mina projected into its void an epic adventure of her own making. Bertie was quickly written out of the story, as he so rightly deserved. Mina now became the heroine, who thanks to her wits and beauty, her bravery and wisdom, rarely suffered a tribulation and always, in the end, triumphed…

© Hope Jennings, Nostalgia (Anti-Oedipus Press, 2015).