So, my discussion of Tennyson here is mostly based on my personal (rather than scholarly) reading of the poems I’ve selected from his extensive body of work. I’m generally not a fan of Tennyson, but I’ve always enjoyed these specific poems and they work really well in the context of the other readings from the first unit. Placing “The woman’s cause is man’s” alongside “Mariana” and “Now Sleeps the Crimson Petal” (as well as “Tears, Idle Tears”) allows for a more complex understanding of Tennyson and his representation of women’s “proper” roles in tandem with Victorian views concerning female sexuality and the burgeoning suffrage movement. Moving from “Mariana” to “Crimson Petal” to “The woman’s cause” seems to follow an increasingly complicated and ambiguous trajectory with regards to the poet’s own developing opinions concerning male-female relationships; yet, all three poems seem to articulate the same thing: a woman’s identity, value, place, and desire can only be defined in her relation to men. This, of course, was a predominant Victorian view, but I think we do see Tennyson trying to work through this and come up with something more progressive, at least considering the time in which he wrote

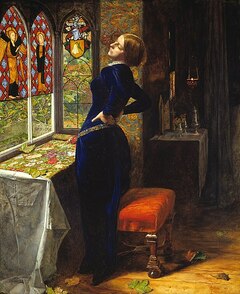

| John Everett Millais, Mariana (1851) | In “Mariana,” the woman is an empty shell without the man who has abandoned her, her life left without meaning, and with no hope of regeneration or rebirth. Whether she was abandoned by her husband or lover is incidental, since at this time, an abandoned woman was a “fallen” or lost woman. According to the Victorian rationale (which often continues to influence contemporary views of women, especially in cases of sexual assault), surely it was something she did and not the fault of the man—or, to be an abandoned woman was to be an incredibly vulnerable woman, prey to the “naturally” baser or corrupt qualities of men. |

Strangely, according to this logic, a woman without the protection of a man also gained a kind of “freedom” to fall—either into despair/melancholy, like Mariana, or an unseemly voluptuousness of desire without anything to keep that desire or her emotions in check. The poem is definitely concerned with female desire, but a kind of “rotten” or decaying desire, as indicated by the poem’s imagery. Her expression of deep despair is overwhelming and potentially threatening to the stability of society since her lover will not return (“He cometh not”) to circumscribe her within his own desire. Even if Mariana is confined within her proper sphere—the home—that space is abandoned and corrupt with excessive longing and grief without the male’s presence to counterbalance this; without him, her only desire is to die. Though, in spite of this, perhaps Tennyson was trying to advocate for the vulnerability of such women?? Merely a suggestion….

In any case, this reading of “Mariana” allows for a contrasting yet complementary reading of the other two poems. I would argue that the speakers of “Crimson Petal” and “The woman’s cause” are unquestionably male; however, the attempt to read either speaker as female, as some of my students have done in the past, certainly allows for some interesting interpretations. The woman in “Crimson Petal” is enveloped by the male to the point of being entirely subsumed (a desirable result for the speaker). However, there's this tricky imagery of the female penetrating the male, which seems to reverse what we might expect (in a heterosexual framework, at least). In some ways, though, this inter-penetrative imagery falls in line with the impetus of “The woman’s cause” in its argument that male and female must complement each other.

“The woman’s cause,” as placed within the larger poem sequence of The Princess, does not provide so much an argument for women’s equal rights as it does a reminder to women of their proscribed social, domestic, and intellectual limitations. Princess Ida has attempted to create a female utopia in which women might pursue their education without the interruption (and interfering distraction) of men. Tennyson appears quite prescient in outlining what would become one of the major demands of the women’s movements of the 19th and 20th centuries (though Wollstonecraft had already identified these in the 18th C.): a woman’s right to an education as the only avenue toward true equality. Yet, by the end of The Princess, and specifically in “The woman’s cause,” Ida is firmly put in her place, shown to be a somewhat “monstrous” woman for demanding an education—at least an education not determined by her father or husband. The prince has clearly “corrected” and educated her as to the complementary rather than separate identity that she should fashion in relation to her prospective husband. Ida is safely and soundly contained by the end of the poem via the prince’s lecture; she is enlightened as to the errors of her ways and the poem confirms (albeit unintentionally) women’s necessary complicity with the very system and ideology that oppresses them.

Overall, then, Tennyson seems to progress in his thinking but actually in all three poems he adheres to the predominant views of his day: that men and women have inherent traits that determine their places in relation to each other, an essentialist view that positions women in a desirably submissive role, and without room or space to define herself apart from male desires (or voices) interjecting. Indeed, these poems taken as a whole articulate the qualities that Victorian males might desire in their female counterparts but not necessarily what women might desire for themselves. And in that sense, the poems are very much about male domination—even if expressed as “benevolent domination” (an oxymoron if there ever was one)—at the expense of genuine gender equality, and female desire is if anything a “glimmering ghost.”

That said, I would point out a couple things in Tennyson’s defense, or, at least a couple things that might further complicate our understanding of his work. First, in his willingness to grant women some expression of desire or sexuality, he emphasizes the dangers of repressing sexuality as equivalent to suppressing full human expression, and for that matter, full understanding of sexual relations between men and women. The erotic energy of “Crimson Petal,” even if positioning women in a submissive role, still allows women some kind of role whereas many Victorian texts entirely negate the presence of sexuality or the act of sex. For example, in many Victorian short stories/novels, such as Gaskell’s “The Nurse’s Story,” women suddenly seem to produce babies without any warning or indication that they’ve had the prerequisite sex to make that biological phenomenon possible (another apt example is Cathy in Wuthering Heights). So, let’s at least give Tennyson some credit in his attempts to make visible that women do have desires, even if those desires are not exactly on par with our contemporary notions of “liberated” sexuality. Although there is something about these poems that is incredibly seductive in their appeal to romantic fantasies, we should not forget that those sentiments expressed toward the desire of finding one’s romantic or domestic “soul mate” are nevertheless constructed on unequal terms.

Lastly, and just as an aside, we might also explore a different, possibly “queer” reading of these poems. Many critics have interpreted Tennyson’s identification with abandoned, desperately yearning women as an expression of his own “feminine” desires. Much of his work can be read as testaments to his lifelong mourning for the loss of his closest friend, Arthur Hallam, who died quite young. Subsequently, through this interpretive approach, Tennyson’s own homoerotic desires are given voice through female characters such as Mariana or the speakers of “Tears, Idle Tears” and the “Crimson Petal.”

For anyone interested, The Crimson Petal and the White by Michel Faber is a rich “neo-Victorian” novel that takes Tennyson’s poem as inspiration for a complex tale that examines from a contemporary perspective the dichotomy of the “Angel in the Home” (white petal) and the “Fallen Woman” (crimson petal), while brilliantly disrupting our notions of these along the way. Definitely a great novel, but like many Victorian novels, a monstrously long read. There’s also a very good and “faithful” four-episode adaptation of the book made for the BBC (and now available streaming) in case anyone wants to supplement their understanding of the many themes and issues we are discussing in this class; though of course I highly recommend you read the book at some point, even if you watch the film version prior to this.

In any case, this reading of “Mariana” allows for a contrasting yet complementary reading of the other two poems. I would argue that the speakers of “Crimson Petal” and “The woman’s cause” are unquestionably male; however, the attempt to read either speaker as female, as some of my students have done in the past, certainly allows for some interesting interpretations. The woman in “Crimson Petal” is enveloped by the male to the point of being entirely subsumed (a desirable result for the speaker). However, there's this tricky imagery of the female penetrating the male, which seems to reverse what we might expect (in a heterosexual framework, at least). In some ways, though, this inter-penetrative imagery falls in line with the impetus of “The woman’s cause” in its argument that male and female must complement each other.

“The woman’s cause,” as placed within the larger poem sequence of The Princess, does not provide so much an argument for women’s equal rights as it does a reminder to women of their proscribed social, domestic, and intellectual limitations. Princess Ida has attempted to create a female utopia in which women might pursue their education without the interruption (and interfering distraction) of men. Tennyson appears quite prescient in outlining what would become one of the major demands of the women’s movements of the 19th and 20th centuries (though Wollstonecraft had already identified these in the 18th C.): a woman’s right to an education as the only avenue toward true equality. Yet, by the end of The Princess, and specifically in “The woman’s cause,” Ida is firmly put in her place, shown to be a somewhat “monstrous” woman for demanding an education—at least an education not determined by her father or husband. The prince has clearly “corrected” and educated her as to the complementary rather than separate identity that she should fashion in relation to her prospective husband. Ida is safely and soundly contained by the end of the poem via the prince’s lecture; she is enlightened as to the errors of her ways and the poem confirms (albeit unintentionally) women’s necessary complicity with the very system and ideology that oppresses them.

Overall, then, Tennyson seems to progress in his thinking but actually in all three poems he adheres to the predominant views of his day: that men and women have inherent traits that determine their places in relation to each other, an essentialist view that positions women in a desirably submissive role, and without room or space to define herself apart from male desires (or voices) interjecting. Indeed, these poems taken as a whole articulate the qualities that Victorian males might desire in their female counterparts but not necessarily what women might desire for themselves. And in that sense, the poems are very much about male domination—even if expressed as “benevolent domination” (an oxymoron if there ever was one)—at the expense of genuine gender equality, and female desire is if anything a “glimmering ghost.”

That said, I would point out a couple things in Tennyson’s defense, or, at least a couple things that might further complicate our understanding of his work. First, in his willingness to grant women some expression of desire or sexuality, he emphasizes the dangers of repressing sexuality as equivalent to suppressing full human expression, and for that matter, full understanding of sexual relations between men and women. The erotic energy of “Crimson Petal,” even if positioning women in a submissive role, still allows women some kind of role whereas many Victorian texts entirely negate the presence of sexuality or the act of sex. For example, in many Victorian short stories/novels, such as Gaskell’s “The Nurse’s Story,” women suddenly seem to produce babies without any warning or indication that they’ve had the prerequisite sex to make that biological phenomenon possible (another apt example is Cathy in Wuthering Heights). So, let’s at least give Tennyson some credit in his attempts to make visible that women do have desires, even if those desires are not exactly on par with our contemporary notions of “liberated” sexuality. Although there is something about these poems that is incredibly seductive in their appeal to romantic fantasies, we should not forget that those sentiments expressed toward the desire of finding one’s romantic or domestic “soul mate” are nevertheless constructed on unequal terms.

Lastly, and just as an aside, we might also explore a different, possibly “queer” reading of these poems. Many critics have interpreted Tennyson’s identification with abandoned, desperately yearning women as an expression of his own “feminine” desires. Much of his work can be read as testaments to his lifelong mourning for the loss of his closest friend, Arthur Hallam, who died quite young. Subsequently, through this interpretive approach, Tennyson’s own homoerotic desires are given voice through female characters such as Mariana or the speakers of “Tears, Idle Tears” and the “Crimson Petal.”

For anyone interested, The Crimson Petal and the White by Michel Faber is a rich “neo-Victorian” novel that takes Tennyson’s poem as inspiration for a complex tale that examines from a contemporary perspective the dichotomy of the “Angel in the Home” (white petal) and the “Fallen Woman” (crimson petal), while brilliantly disrupting our notions of these along the way. Definitely a great novel, but like many Victorian novels, a monstrously long read. There’s also a very good and “faithful” four-episode adaptation of the book made for the BBC (and now available streaming) in case anyone wants to supplement their understanding of the many themes and issues we are discussing in this class; though of course I highly recommend you read the book at some point, even if you watch the film version prior to this.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed