I’m mainly going to focus on Swinburne here, since his work can be quite challenging for students. The Swinburne poems that we read this week also help highlight some of what we will encounter in the modernist period. For instance, like many modernist poets, Swinburne’s allusions to Greek mythology might be read as a rejection of Victorian/Christian mores and a recovery of pagan or classical frameworks signifying a world that is more stable—in its longer, historical tradition—yet equally fluid, at least in opposition to Victorian gender binaries and repressive attitudes toward nonnormative sexualities. The return to Greek and Roman classicism—and at times, a turning away from Western culture to traditions of the East—is also expressed as a form of anxiety in the face of a rapidly changing modern world and a fragmented, alienated sense of self in the devastating aftermath of the First World War. So, yes, the return to paganism for Late Victorians (and modernists) was on some level “escapist” and provided a nostalgic return to a seemingly simpler, more sensuous, prelapsarian innocence (i.e. before the Fall), a time when sexual desires supposedly had a greater range of free expression.

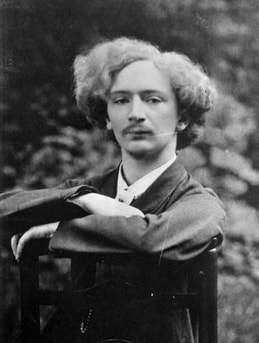

All of which was a romanticization of Greek and Roman societies, which were just as hierarchical and restrictive in setting up their own separate spheres between the sexes, where only free men had access to the public sphere, free discourse, and the option to explore homosexuality or bisexuality. Indeed male/male relationships (homosocial as opposed to homosexual relationships) were considered the ideal; if men were to seek out the female society of gynaekes (wives), this was simply for procreative or domestic relationships, and if a man wanted sexual pleasure or intellectual companionship from a woman, then there were the hetaera (educated courtesans), and on a lower rung pallakide (mistresses), and, below that pόrne (prostitutes). For example, as noted by Demosthenes:“We have hetaerae for pleasure, pallakae to care for our daily body’s needs and gynaekes to bear us legitimate children and to be faithful guardians of our households” (Wikipedia) (yes, sometimes I use Wikipedia for quick reference, but if you’re interested in reading something more scholarly, one of my former teachers at Hunter College, Sarah B. Pomeroy, has a great book on this topic, Goddesses, Whores, Wives, and Slaves: Women in Classical Antiquity ). Ironically, then, this romanticized return to so-called paganism and/or the classical world was in fact quite reassuring of Victorian social structures and assigned sexual roles for women and men. Nevertheless, if one were to focus solely on the Greek gods and goddesses then certainly these provided an outlet for more passionate and liberal sexualities, and so of course they might appear attractive to an author attempting to explore “other” sexualities or identities.

Hetaera, Phintias Painter, c. 510 BC

Thus, Swinburne and “Michael Field” (a pseudonym for the poets and playwrights, Katherine Bradley and her niece, Emma Cooper) are pressured to disguise same-sex desires through coded language and mythologies, especially if we consider that homosexuality was illegal and one could be imprisoned for it or publicly censured—for example, the infamous Oscar Wilde trials and the scandal surrounding Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness (a 1928 novel depicting a lesbian relationship). Fortunately, we see during the modernist period authors increasingly taking the risk to write about same-sex desire even if they remained “closeted,” for instance Virginian Woolf and E. M. Forster, whose work we’ll be reading next week. By taking these risks, such writers contributed through literature to the increasing socio-cultural acceptance of non-hetero romantic love and sexual identification, or, if not entirely accepted, at least the gains in freedom of speech to write or speak of same-sex desires and relationships without having to disguise it to the point of near-invisibility.

So, considering Victorian contexts, even if during the fin-de-siècle period where there was a (slight) loosening of gender roles/relationships, it’s no surprise that Swinburne’s poetry is densely symbolic, much of which is used to “veil” sentiments or desires not condoned by Victorian norms and legalities. Likewise, Cooper and Bradley employ a male pseudonym to veil the authors’ relationship, which was not only transgressive as a lesbian partnership but one that was also incestuous (indicated in the authors’ bios). Borrowing from Sapphic tradition, as grounded in Sappho’s fragmented texts (because fragments are all that survived antiquity) and the corresponding myths constructed around a woman poet about whom very little is known, this also provides “Field” with some authority for establishing a separate sphere comprised wholly of female desire, companionship, and love. In this sense, yes, Cooper and Bradley reinforce the ideology of separate spheres but in a way that subverts and redefines it.

So, considering Victorian contexts, even if during the fin-de-siècle period where there was a (slight) loosening of gender roles/relationships, it’s no surprise that Swinburne’s poetry is densely symbolic, much of which is used to “veil” sentiments or desires not condoned by Victorian norms and legalities. Likewise, Cooper and Bradley employ a male pseudonym to veil the authors’ relationship, which was not only transgressive as a lesbian partnership but one that was also incestuous (indicated in the authors’ bios). Borrowing from Sapphic tradition, as grounded in Sappho’s fragmented texts (because fragments are all that survived antiquity) and the corresponding myths constructed around a woman poet about whom very little is known, this also provides “Field” with some authority for establishing a separate sphere comprised wholly of female desire, companionship, and love. In this sense, yes, Cooper and Bradley reinforce the ideology of separate spheres but in a way that subverts and redefines it.

In “Hemaphroditus,” Swinburne also attempts to redefine, and more obviously reject, the separation between the sexes, showing where the two blend, yet this blending is also remarked upon as “sterile”—thus hinting at a common view of same-sex desire in contrast to reproductive sexuality. In “Hymn to Proserpine,” the male speaker wholly identifies with a female goddess and by extension a feminine-maternal realm. Whether accurate or not, this is something often observed of gay men or gay culture when homosexuality is read as a general rejection of a patriarchal system, since to identify with “the feminine” can be incredibly subversive in a world where “the masculine” is set up as the norm: to identify with the masculine is to gain access to power and inherent value, based on the oppression/suppression of the feminine; to reject the masculine is to reject phallic power and privilege over female bodies. Lesbian desire is also subversive in a similar way in its rejection of the patriarchal “law” that dictates and relies upon female bodies as objects of male desire, or, as objects of exchange or currency between men.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Proserpine, 1874

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Proserpine, 1874

Of course, I recognize that we have to dig deep to get at some these buried impulses or desires, and socio-political critiques of patriarchy, as represented in the texts (especially Swinburne’s texts), but if we take the time to make these kinds of textual excavations then our understanding of such texts and the cultures/societies that produce them are in many ways expanded and enriched. As for the rest of the week’s assigned reading, although these are a bit lengthy (one a comedy of manners and the other a gothic novella), they should be a little “easier” to grapple with, though the depictions of late Victorian masculinities and homosocial relationships in The Importance of Being Earnest and Jekyll and Hyde will offer deeper insights into the earlier texts from this week as well as helpful transitions to themes explored over the next few weeks in our readings of modernist and contemporary texts.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed