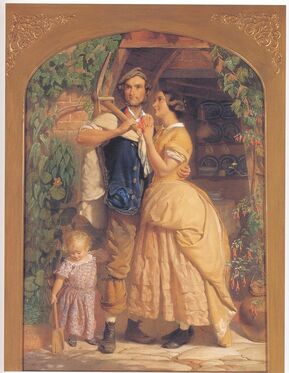

Image: The Sinews of Old England (1857) by George Elgar Hicks shows a couple "on the threshold" between female and male spheres (Wikipedia)

The readings from this first week explore the complexity of Victorian views when attempting to answer the "Woman Question." As we see from John Stuart Mill and Florence Nightingale, both men and women during this time refused the status quo by challenging the perceived "natural" division between the sexes. And, as John Ruskin, Coventry Patmore, and Sarah Stickney Ellis reveal, both men and women were responsible for reinforcing the gender norms of the time through their insistence that women "naturally" belonged in the private sphere. The selections of poems by Alfred, Lord Tennyson's and Elizabeth Gaskell's short story provide somewhat opposing gendered views, yet, you should also pay attention to the internal tensions and contradictions in each of their works for what they reveal about the complexities of 19th Century gender roles, as well as views concerning female sexuality, which weren't really touched upon in the essays.

Although we often have a popular perception of the Victorians as ridiculously repressed and conservative, they were often intensely preoccupied with defining and containing female sexuality by reinforcing gendered binaries that intersected with class divisions. These binaries severely limited women's identities to two opposing archetypes: either the "Angel in the Home" (private sphere) or the "Fallen Woman" (public sphere). In other words, the construction of separate spheres did not just apply to perceived differences between men and women, but also differences between women. On the one hand, you had the desexualized and morally pure Wife/Maiden and on the other, the sexually threatening and morally corrupt Prostitute. Thus, the theory of separate spheres provided very little space for real women to maneuver between these two extremes.

Also, it should be noted, by placing women on such high pedestals (as "Angels"), thus obligating them to be no less than perfect, this essentially keeps women subjugated to an impossible ideal while erasing or silencing their realities, their persons, and their multifaceted desires and capabilities (and flaws). J. S. Mill's argument is perhaps one of the most balanced and perceptive in its observation that despite all that was written about women, very little was actually known or understood about women because women were rarely given the opportunity to speak or write about their lives and experiences. Indeed, Mill's argument, following Mary Wollstonecraft's A Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792), was influential on 20th C. writers and feminist philosophers. For instance, as French feminist Hélène Cixous claimed in her essay, "The Laugh of the Medusa" (1975): "Woman must write herself. ... [She] must put herself into the text—as into the world and into history—by her own movement."

So, as we proceed through the 19th and 20th centuries, we shall see how women increasingly began doing this, and how some often resisted a "women's movement" while others, including men, increasingly began to question (and subvert) social constructions of gender. Lastly, it's important to keep in mind that the Victorian era was one that saw a series of social reform acts, including incremental changes in child custody, divorce, and marital law, all of which helped pave the way for the suffrage and feminist movements of the 20th Century.

Although we often have a popular perception of the Victorians as ridiculously repressed and conservative, they were often intensely preoccupied with defining and containing female sexuality by reinforcing gendered binaries that intersected with class divisions. These binaries severely limited women's identities to two opposing archetypes: either the "Angel in the Home" (private sphere) or the "Fallen Woman" (public sphere). In other words, the construction of separate spheres did not just apply to perceived differences between men and women, but also differences between women. On the one hand, you had the desexualized and morally pure Wife/Maiden and on the other, the sexually threatening and morally corrupt Prostitute. Thus, the theory of separate spheres provided very little space for real women to maneuver between these two extremes.

Also, it should be noted, by placing women on such high pedestals (as "Angels"), thus obligating them to be no less than perfect, this essentially keeps women subjugated to an impossible ideal while erasing or silencing their realities, their persons, and their multifaceted desires and capabilities (and flaws). J. S. Mill's argument is perhaps one of the most balanced and perceptive in its observation that despite all that was written about women, very little was actually known or understood about women because women were rarely given the opportunity to speak or write about their lives and experiences. Indeed, Mill's argument, following Mary Wollstonecraft's A Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792), was influential on 20th C. writers and feminist philosophers. For instance, as French feminist Hélène Cixous claimed in her essay, "The Laugh of the Medusa" (1975): "Woman must write herself. ... [She] must put herself into the text—as into the world and into history—by her own movement."

So, as we proceed through the 19th and 20th centuries, we shall see how women increasingly began doing this, and how some often resisted a "women's movement" while others, including men, increasingly began to question (and subvert) social constructions of gender. Lastly, it's important to keep in mind that the Victorian era was one that saw a series of social reform acts, including incremental changes in child custody, divorce, and marital law, all of which helped pave the way for the suffrage and feminist movements of the 20th Century.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed