Similar to the speaker in Mina Loy’s “Songs to Joannes,” Mrs. Dalloway and Molly Bloom both find male dominance and sexual submission to be oppressive. In this sense, they both subvert typical representations of female desire and sexuality. Although both women’s marriages seem to be defined by a lack of sexual intimacy and unfulfilled, repressed desires, they share in common a rich inner life and sensuality. An interesting connection between the two women is their love of flowers, which symbolize for both of them that (lost) connection to their sexuality, or, a kind of sublimated form of their sexual desires which finds expression in a love of nature. For example, although Dalloway is fully immersed in her urban surroundings—the “throb” and “hum” and “teeming, pulsing life” of the city thrills her—yet she repeatedly returns to memories of her childhood country home and her intimate friendships with Sally and Peter. Likewise, Molly keeps returning to memories of her youth in Gibraltar: the sea and meadows and flowers in the final passages of her soliloquy. Both women feel cut off from their maternal sides as they are also cut off from nature, which of course leads some to interpret at least Molly (not so much Clarissa) to be an earth mother figure, though I think this oversimplifies or essentializes the representation of femininity in the text, and undermines the complexity of Joyce’s characterization of Molly Bloom.

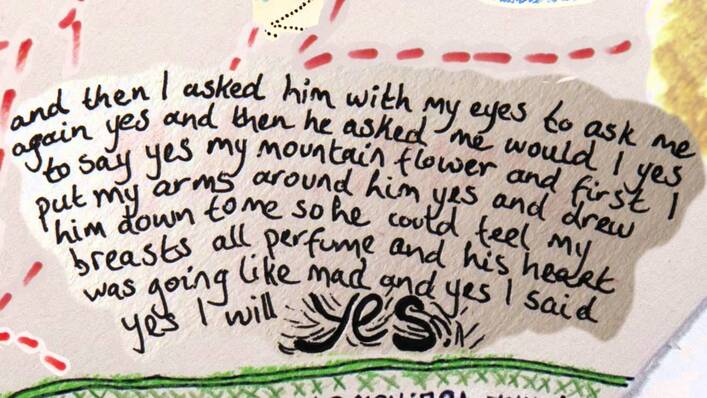

Molly may be “earthy” and “maternal” but she is also “vulgar” and sexually passionate and refreshingly expressive about her desires, far more so than most women of her day, or even our own, are allowed to be. Joyce does a fascinating job of slipping into a “feminine” language, thought-process, and perspective on the nature and expression of female desire (or at least Molly’s desires). She is in many ways more accurately an anti-Penelope (Ulysses’ loyal wife in The Odyssey). Molly’s soliloquy is marked by her sexual explorations rather than rigid virtue—though in some ways she’s very much like the mythical Penelope in her romantic fidelity to Leopold—and perhaps her infidelity is due to the possibility that Molly feels Leopold has in some way failed a “test” in their marriage (thus making him a kind of anti-Ulysses). And though yes, Molly has had sex with Blazes earlier that day, we don’t get the sense that she is going to continue the affair. The lack of affection and intimacy during their sexual encounter has actually left Molly cold and longing to reignite and reaffirm her sexual connection with her husband, who is shown throughout the text, in spite of his own vulgarities and infidelities, to be nurturing, sensitive and still deeply in love with his wife. Significantly, by the end they have both “come home” to each other (a term that also has sexual connotations), and although they don’t have sex, the orgasmic conclusion to Molly’s soliloquy is an orgasmic “Yes” to life, desire, and their marriage. Ironically, then, Joyce stays true to the original narrative of Ulysses while also modernizing it.

Image Credit: University College Dublin

There’s more I could say here about Ulysses but that would also require getting into the larger scope and action of the novel, which is not entirely necessary to our purposes, since we of course have not read the entire novel but only a very small selection, though one of the most important sections. I’ve said more here about Molly Bloom than Clarissa Dalloway mainly because I think Woolf’s character and writing style is a bit more accessible, at least more so than Joyce’s often challenging stream-of-consciousness. A good approach to reading Molly’s soliloquy is to relax and let our own minds go, or, our desire for immediate sense and logic to the structure of her thoughts; in this way we might gain a greater understanding or “feel” for the rhythms of internal thought and desire as these play out in Molly’s and our own conscious. Like the seemingly disjointed associative patterns in Molly’s soliloquy, we too are not always aware of the leaps and connections we make from one thought to the next.

On some level, we find a similar exploration of the subconscious in Forster’s short story, "The Other Boat," though it is not at all written in the more experimental stream-of-consciousness used by Woolf and Joyce. Forster allows for us to “read” the inner thoughts, desires, and perspectives of both Lionel and Cocoanut, hence allowing for a more enriched and complex understanding of the interplay between sexuality, race, gender, and class—and how these create connections and tensions between the two characters. This text’s construction of “otherness” demonstrates how men are often more stigmatized for homosexuality, and a primary reason for this, as theorized by various feminist thinkers, is because gay men in their same-sex desires are stepping outside or rejecting a system that relies on dominance over and exchange of female bodies (as I mentioned in my discussion of Swinburne). However, according to my own reading of the text, Forster also disrupts this theory, particularly in Lionel’s violent rage toward Cocoanut, the “feminized” other, and perhaps also because Lionel fears the ways in which he has become feminized. This homophobic fear, or internalized homophobia, is revealed explicitly in Lionel’s reaction to Cocoanut’s joke about “tipping” him as if he were a prostitute, which seems to be the instigating moment that begins the unraveling of their intimacy, leading Lionel to get up from the bed and notice the unbolted door (a wonderful symbol for his fear of exposure and becoming “uncloseted”). To recover his own sense of control and power, Lionel is then reduced to savagery and destruction of the other, itself shown quite explicitly by Forster to be connected to self-destruction – this also connects to Forster’s critique of imperialism.

In closing, a note about some of the outdated and offensive terms that appear in Forster’s story, such as “mulatto,” “half-caste,” “wog,” and “dago." These are all examples of how specific words contain a history of racism and oppression, and I think Forster uses them quite sarcastically and bitterly in his rejection of the “Ruling Race” (the British) and its own sense of racial superiority. Forster’s use of language here highlights the constructed differences between the “West” and its fantasized or projected “others” (see Edward Said's seminal study, Orientalism). Keep some of this in mind for next week’s reading, Heart of Darkness, and think about how Conrad’s text explores the various ways in which language is used as a colonizing force.

E. M. Forster, by Dora Carrington, c. 1924–1925

In closing, a note about some of the outdated and offensive terms that appear in Forster’s story, such as “mulatto,” “half-caste,” “wog,” and “dago." These are all examples of how specific words contain a history of racism and oppression, and I think Forster uses them quite sarcastically and bitterly in his rejection of the “Ruling Race” (the British) and its own sense of racial superiority. Forster’s use of language here highlights the constructed differences between the “West” and its fantasized or projected “others” (see Edward Said's seminal study, Orientalism). Keep some of this in mind for next week’s reading, Heart of Darkness, and think about how Conrad’s text explores the various ways in which language is used as a colonizing force.

E. M. Forster, by Dora Carrington, c. 1924–1925

RSS Feed

RSS Feed